(Continued from the previous issue. . .)

3

Let us now examine what each account expresses or actually reveals about Sri Ramakrishna.

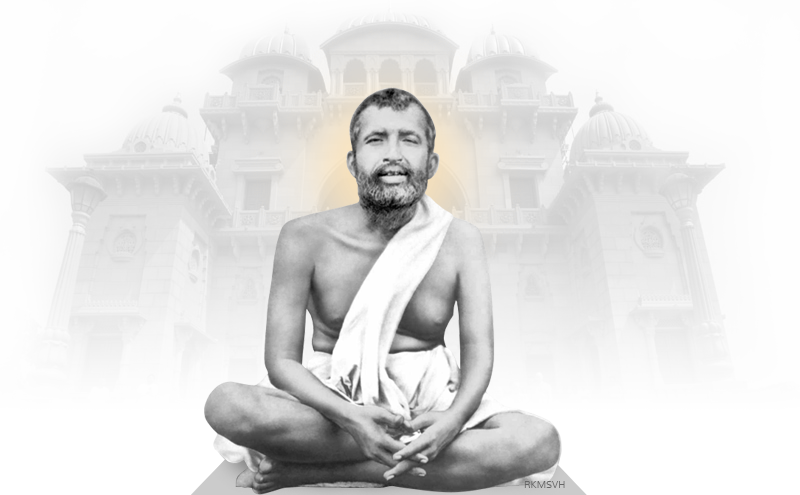

In the Great Master, Swami Saradananda mentions a number of traits that Sri Ramakrishna manifested in his childhood and youth that are significant indicators of his developing attitudes that influenced his entire life. In this context, ten characteristics may be mentioned: his remarkable memory and intelligence; loving nature; willfulness; determination; truthfulness; rationality; artistic temperament; keen imagination; fearlessness; and purity.

Although this is by no means an exhaustive list, these basic characteristics encompass all others forming the foundation of his character. And from this foundation, we get an idea through some of the incidents and examples that Swami Saradananda gives from Sri Ramakrishna’s life experiences of how he was molded, humanly speaking, into the person that he was. Although dreams and visions prior to his birth were indicators of his divinity, nevertheless, the lila or human-divine play manifested fully throughout his life.

His penetrating intellect and preternatural insight revealed many truths which generally remain hidden to the ordinary mind, covered as it is with maya’s veil. But through his uncanny insight, even as a child and youth, he saw into the heart of everything. Nothing escaped his keen eye and sharp power of observation. As a result, he developed an unusual prescience concerning the transitory nature of the world.

His loving, thoughtful ways endeared him to all his relatives, playmates, and the villagers who came into contact with him. He was friendly with everyone. Considerate and gentle, he avoided any words or behavior that might wound another’s feelings. He never injured any being, even mentally. Whenever he spoke to anyone, he said what was true, pleasant, and helpful to others.

His truthfulness, fearlessness, and guilelessness manifested in every moment of his life. Truth was the fabric of his being. He was simplicity itself; it was impossible for him to conceal anything. As a result, he was totally fearless, courageous, and strong. What or whom to fear when one has nothing to hide? Everything about his personality was transparent; his mind was as the Bhagavad Gita mentions, prakasakam anamayam (14:6), luminous, healthy, and cheerful. Because the sattva quality was overwhelmingly predominant in him, he was well-integrated, steady, and balanced, prasantadhih. This mentally expansive state expressed through all the faculties of his mind: cognition, perception, understanding, will, and his selfidentity.

All of his natural characteristics and inclinations, from his extraordinary intelligence, purity and simplicity, love and compassion for all, stubborn independence, to his ecstatic artistic temperament, enabled him to extract from ordinary everyday examples the most profound truths, and to convey these truths in a sweet appealing way. And the fact that he transparently embodied those truths, made every word he spoke, every action he undertook, redolent with divine knowledge. This is why when we study Sri Ramakrishna’s personality, we are able to find the divine manifest fully in human form, a rare and most astonishing occurrence in the spiritual realm.

The Great Master gives a sweeping picture of the comprehensive exalted spiritual experiences and breadth of visions that Sri Ramakrishna had from his childhood to the last days of his life culminating in his mahasamadhi. Swami Saradananda has thoroughly examined and analyzed every step of his sadhana, including a detailed description of his training under various gurus of different traditions. As a result of his wide-ranging experiences, Sri Ramakrishna had a vast, infinite reservoir of knowledge in which he dipped frequently bringing life-giving nectar to spiritual seekers of all ages, faiths, and stages of evolution. His simple instructions, childlike personality, and transforming touch were enough to convince even the staunchest skeptic such as Swami Vivekananda that, ‘God can be seen.’

God for Sri Ramakrishna was a living, luminous presence in which he joyously dwelled as naturally as he breathed. Infinite Being is boundless, without boundaries, nameless, formless, without qualities, yet endowed with innumerable forms, names, and qualities. In the words of the Isa Upanishad (v.5): ‘tadejati tannaijati taddure tadvantike tadantarasya sarvasya tadu sarvasyasya bahyatah.’ ‘It moves and moves not; it is far and likewise near. It is inside all this and it is outside all this.’ His realizations encompassed all states of consciousness as manifestations of the one akhandasatchidananda. The Master said everything, including all the scriptures of the world, have been uchchishta, defiled, by the tongue; pure Being, the absolute Brahman, which is beyond thought and word, remains undefiled because from it speech and mind turn back, ‘yato vacho nivartante’ (Taittiriya Upanishad 2:9). As he related many times, only an indication of the absolute Being can be given. He would tell his disciples, ‘I want to tell you everything, but someone holds my tongue.’

In The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna we find similar observations, yet the expression of these varies because of the conversational format and circumstances under which the Gospel was recorded, as opposed to the narrative style of The Great Master. In and through all the teachings given through his conversations, a unique picture of Sri Ramakrishna is disclosed. The Master was forty-six years old when M. met him. He would live only another four years. All his experiences, that vibrant touch of the soul, which had accumulated throughout his years of sadhana are revealed through his words, which are enlivened by his life. Day and night he was lost in God-consciousness. Those who were fortunate enough to witness his Godintoxicated state and divine moods that kept him absorbed in blissful awareness could form some idea of what it means to live in God, to become one with Him.

M. once said that a spiritual mood was the natural state of Sri Ramakrishna’s mind. Although he tried to keep his mind at the phenomenal level for the sake of others, the intensity of his experiences would elevate him to the highest levels of consciousness, but when his mind returned to this relative world, he found everything was infused with divine consciousness as well. ‘Sometimes,’ he said, ‘I find that the universe is saturated with the consciousness of God, as the earth is soaked with water in the rainy season.’ So, all his words that have been recorded in the Gospel come directly from the depths of his being clearly reflecting the truth.

Once when Sri Ramakrishna was having a conversation with a Vaishnava, he told him that man should possess dignity and alertness. Only one whose spiritual consciousness is awakened possesses these qualities and can be truly called a man. It was as if he were describing himself. Sri Ramakrishna was the essence of dignity; his mind was so alert that he had literally put sleep, to sleep. The Master’s experiences verified the truth that everything is divine. Avidyamaya covers divinity and projects a false identity in its place. He always stressed that worldliness and liberation are in Divine Mother’s hands. It’s all according to her sweet will. As he put it in his homely way, what everyone considers as a human being is only a pillowcase; the consciousness within is the true person. The real person is pure Atman.

One of the keys to understanding Sri Ramakrishna is his immersion in the divine lila, God’s play. The conundrum of life, especially one’s relationship to the divine, is more understandable if everything is put into perspective regarding God’s lila. This whole universe is a manifestation of this play. Through ignorance what we take to be the world with all its multifarious objects, both sentient and insentient, and what we call humanity are only so many manifestations of the same Being. All names and forms are superimposed on this one nondual consciousness.

This profound truth is reiterated in so many different ways, from various angles throughout the Gospel. In every analogy, metaphor, simile, illustration, or story we can find the very truth Sri Ramakrishna is proclaiming reflected directly in his life and personality. He was one with the truth he spoke about. Therefore contemplating his words gives us direct access to who he was. God alone, he would say, has become the universe, living beings, and the twenty-four cosmic principles. Brahman is actionless; but when creating, preserving, and destroying, it is shakti. Brahman and shakti are identical. Water is water, whether it is still or flowing.

Again, what’s to be gained by merely hearing or speaking about God? What is needed is becoming intuitively aware of God’s presence within us and all around us. You have to bring him into your room and talk to him. Here, Sri Ramakrishna is giving us direct access into the mystical realm. We have to drink milk and assimilate it, not just describe its qualities. Seeing Benares is entirely different from merely hearing or reading about it. Some people have seen the king, but how many can bring him to their home and entertain him? God is our very own; he is not a stranger to us but is our own inner Self.

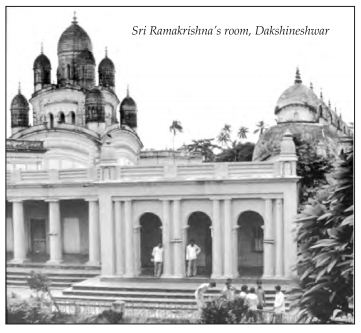

Often we find in the Gospel when the Master is trying to describe the vision of God or some other inner experience, he would enter into samadhi. In unguarded moments, Sri Ramakrishna would reveal that God alone dwelled inside his body, that he was pure consciousness. He said that the Divine Mother had revealed to him in the Kali temple that everything—the image, himself, the utensils of worship, the doorsill, the marble floor—is chinmaya, the embodiment of Spirit. His human form infused with joy appears to be floating over an ocean of infinite consciousness.

In conclusion, it may be said that both Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lilaprasanga and Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita are unique expressions of Sri Ramakrishna. Swami Saradananda critically analyzed all the aspects of the Master’s life specifically within the social and cultural tenor of the times, whereas M. recorded actual conversations between Sri Ramakrishna and those who visited him during the last four years of his life when the diary was written. Although the social and cultural settings are present in the diary, it is given more as a background for the conversations.

The Great Master includes the formative years of Sri Ramakrishna’s life, as well as an account of his extensive sadhana and resulting experiences, while the Gospel contains the words of one who was not only a highest knower of God, brahmavaristha, one who had become Brahman, ‘brahma veda brahmaiva bhavati,’ (Mundaka Upanishad, 3.2.9), but also one who was avataravarishtha, supreme among all divine incarnations. All of his previous observations and conclusions that he had derived years before concerning humanity, God, and spiritual life flow in an unbroken stream to those who came to see and hear him. It is almost as if the Gospel is the practical application of all that is mentioned in The Great Master. Though these two portraits of the Master are diverse in content, yet in essence each complements the other. If studied together, a more complete, expansive picture of who Sri Ramakrishna was will be revealed.

(Concluded.)

References

M, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, trans. Swami Nikhilananda (New York: RamakrishnaVivekananda Center, 1969).

Swami Saradananda, Sri Ramakrishna: The Great Master, trans. Swami Jagadananda (Madras: Sri Ramakrishna Math, 1952).

Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita: Centenary Memorial (Chandigarh: Sri Ma Trust, 1982).

Swami Chetanananda, Mahendra Nath Gupta (M.): The Recorder of the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, (St. Louis: Vedanta Society of St. Louis, 2011).

Approaching Ramakrishna: In Commemoration of the 175th Birth Anniversary of Sri Ramakrishna (Kolkata: Advaita Ashrama, 2011).

Source : Vedanta Kesari, May, 2016