—The First Centenary Celebration of Sri Ramakrishna’s Birth

(Continued from the previous issue. . .)

The following article, of much archival and documentary significance, is based on a recorded talk given in the early 1960s by late Swami Sambuddhananda (1891-1974) at the Vedanta Society of Hawaii in Honolulu, USA. This very interesting and informative talk has been thoroughly edited by Swami Bhaskarananda, the Head of Vedanta Society of Seattle, USA. It was first published in Global Vedanta, the English quarterly published from there.

The Bengali message sent by our President [Swami Akhandananda] had to be translated into English as fast as possible. We had only two days left for translating the message and sending it abroad by cablegram. We knew one of the translators at the High Court of Calcutta. Since the translation had to be authentic, we requested him to translate the message. If he could do the translation that same day, we would still be able to send it by cablegram to America and Europe in time.

When we took the translated message to the telegraph office in Calcutta, the telegraph operator said that in the entire history of their office they had never received such a lengthy cablegram. We had to spend a lot of money to send that cablegram. As far as I recall, they charged us at least one rupee for each word. [Editor’s note: To satisfy the curiosity of the readers, we give below the entire text of Swami Akhandananda’s message about Sri Ramakrishna]:

This time the Lord was born in a hut. His superhuman austerities, His sadhana and its culmination, the extraordinary powers and realizations all took place on the sacred banks of the Ganga, under the wide-spreading boughs of the Panchavati and the Bel tree. The Sikh sentinels who kept guard over the Government powder magazine with drawn swords, just to the north of the sacred Dakshineswar, had the enviable good fortune to witness the various sâdhanâs of the Lord, which were hidden from other men. It is from these Sikh guards that the Lord came to be known by the public, that is, the Marwaris of Burrabazar.

It was at the Panchavati that He cried out in pain, ‘They are beating me!’ when a bullock was being beaten, and a welt was seen across His back. Here it was that He fell to the ground as He saw a heavy log being dragged across a field of tender grass. This is the culmination of universal love.

That blessed day is not far off when we shall be illumined by His glory. Through the Lord’s wonderful harmony of all religious ideas—the paths of action, knowledge, devotion, and meditation—the human race is advancing, knowingly or otherwise, towards salvation. That blessed day is coming when peace will reign all over the world, when all humanity, at the Lord’s call, will shun petty quarrels, will hold unto Truth and, with its inspiration, make known with trumpet voice the Lord’s message: ‘As many faiths, so many paths,’ and gather under the banner of the new age. Then will the whole world be blessed by realizing the purpose of the Lord’s advent. This is my fervent prayer. Svasti! Svasti! Svasti! (Peace to the world!)

After sending the cablegram, we all heaved a sigh of great relief. Then we wondered what had changed Swami Akhandananda’s mind regarding his giving a message for the Centenary! Nobody, not even Miss MacLeod could persuade him to do that!

Now I’ll tell you what actually happened: Swami Akhandananda as usual went to sleep. He went to his bedroom and fell asleep. At about one o’clock he came out of his bedroom and started calling some monks. To one he said, ‘Please bring my pen.’ To another he said, ‘Bring some notepaper. Bring the lantern.’5 When they brought those things, he sat down and started writing his message.

After writing it he told the monks what had happened. At about one o’clock in the morning, when he was still in bed, Sri Ramakrishna appeared before him. Sri Ramakrishna said to Swami Akhandananda, ‘Gangadhar! My children have been organizing a Centenary Celebration all over the world. What does it matter to you if you write a few words by way of your blessing to the whole world?’ By the way, Swami Akhandananda’s pre-monastic name was Gangadhar.

Swami Akhandananda was startled. He got up and saw Sri Ramakrishna fading away after saying those words.

This is how the most important need for the celebration came to be fulfilled. Unfortunately, even before the commencement of the celebration, Swami Akhandananda passed away and Swami Vijnanananda became our President. The Parliament organized by the Centenary Committee started on the 1st of March and ended on March 8th, 1937. Swami Vijnanananda attended the Parliament of Religions, particularly in its evening sessions. He used to sit silently watching the deliberations of the Parliament. In this way the Celebration continued.

As mentioned before, many famous people willingly joined the celebration. However, the cooperation of India’s Nobellaureate poet Rabindranath Tagore had to be secured by us with great difficulty. I went to him and requested him to preside over only one of the meetings at the Parliament of Religions. There were 14 meetings. And the persons who had agreed to preside over them were all big people, not only of India, but also of Europe, America and so forth.

When I approached him, Tagore told me, ‘Swamiji, my experience is that whenever I’ve gone to speak at any meeting, I’ve only seen indiscipline and chaos. Sometimes people even fight with one another, causing bloodshed. Would you like me to experience another scene of bloodshed at your celebration?’

Then I told him, ‘Well, I can assure you that nothing of that kind will happen.’

‘Where is the meeting going to be held?’ he asked.

I replied, ‘The meeting will be held at the town hall.’

He said, ‘I won’t be able to go there, because there is a staircase to climb. I won’t be able to climb up the stairs.’

Then I asked him, ‘Well, would you like the meeting to be held at the University Institute Hall? The meeting will be held on the ground floor. You won’t have to climb any stairs there.’

He agreed to be the President in the afternoon session of the Parliament to be held on March 3rd, 1937. So I went straight to the office of the University Institute Hall. They told me that the hall would not be available, because another party had already booked it for that particular day. What could I do? I then approached the party that had booked the hall and explained to them the urgency of our need. After much persuasion the party agreed and changed their date of booking. So we got the hall.

We had an Indian friend who had been in Europe and America several times and was married to a German lady. He was one of the volunteers at our Centenary office. I had made him the Secretary of the Parliamentary Subcommittee. One day he told me, ‘Swamiji, there is one difficulty. Some Brahmos are not in favor of our holding the Parliament of Religions.

‘The Commissioner of Calcutta Corporation is a Brahmo, and he is dead against us. The Brahmos couldn’t celebrate their leader Rammohun Roy’s birth centenary successfully. That’s why the Commissioner cannot tolerate the idea that Sri Ramakrishna’s birth-centenary celebration should be a success. He actually tried to create some problems for us. But in the meeting of the counselors of the Calcutta Corporation all his attempts to harm us were foiled.

‘Tagore is a Brahmo. I am afraid this Brahmo Commissioner may try to influence Tagore by discouraging him from actively participating in our Celebration.’

Even though we rented the University Institute Hall for the meeting to be presided over by Tagore, he [Tagore] lay down many other conditions. One of the conditions was that as he was not keeping well, he would just read his paper, and immediately after that he would go home. He also said, ‘When I leave the meeting, who is going to sit in my place? Who will then act as President?’

So I had to look for another Brahmo person, a famous one at that, who could later occupy Tagore’s Presidential seat. Otherwise Tagore wouldn’t agree to be President.

Our volunteer friend said to me, ‘Swamiji, somehow or the other the Brahmos will try to ruin our function. At the last moment they may persuade Rabindranath Tagore not to come on health grounds. They may use a sudden rise in his blood pressure or something like that as an excuse!’

Therefore, to prevent such a possibility, I first found out the name of Rabindranath Tagore’s family physician. Then through some friends I was able to find out that family physician’s teacher, Dr. Sarkar, who had taught him in medical school. I met Dr. Sarkar and said to him, ‘Will you please accompany me when I go to bring Tagore to preside over our meeting?’ He agreed and went with me. I wanted him to accompany me to take care of a medical emergency, if any. Fortunately, he found nothing wrong with Tagore’s health.

Then Tagore said, ‘Your hall will accommodate only 1500 or 1600 people. But it is quite likely that there may be a crowd of several thousand people wanting to enter the hall. Then what will happen? Those people may make a row outside and create all sorts of trouble. And the meeting will be spoiled.’

I assured Tagore that nothing like that could happen, because we had already put several loud speakers outside the hall, some installed on top of the palm trees of the College Square (a park in front of the University Institute Hall). Even if 25,000 people assembled in that park they would have no difficulty hearing the speeches given inside the hall. Hearing that, Tagore said with much gladness, ‘Swamiji, it’s a very nice arrangement you have made. Now I’m sure that everything will be all right.’

I had already chosen the gentleman who would succeed Tagore as the President of that meeting. He was Ramananda Chatterjee, the editor of The Modern Review. 6 I told Ramananda Chatterjee that he would have to assume the position of the President of the meeting when Tagore would go away. He was extremely pleased to hear it. He said to me, ‘Rabindranath Tagore’s place will be occupied by me! It’s a great honor. I’m immensely pleased.’ Tagore was also pleased to hear that Ramananda Chatterjee had agreed to preside over the meeting after he would leave the meeting.

But in my eagerness to bring Tagore, I forgot altogether to send someone to bring Ramananda Chatterjee to the meeting. Had Tagore seen Ramananda Chatterjee present in the hall, he would at least rest assured that his substitute had come. Thus, he would not be worried. Otherwise he might be anxious thinking who would sit there in his place. So I requested Dr. Sarkar to accompany Rabindranath Tagore and bring him to the University Institute. Meanwhile I rushed to the hall and sent one person to Dr. Chatterjee to bring him by a cab. I told him, ‘Please go at once by a cab to his house and apologize for the delay in bringing him here.’ Meanwhile Ramananda Chatterjee arrived at the Institute, hiring a cab on his own. When I apologized to him he reassured me, saying that he had not minded anything at all.

Just before Rabindranath Tagore was brought to the platform, I found that there was a fight going on between two members of the audience. One had raised a chair to hit the other! Jumping in between them I was somehow able to stop the fight and made the two men sit wide apart.

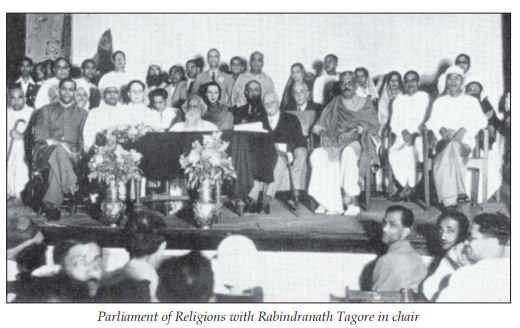

By the time Tagore arrived the hall was quiet and peaceful. After his arrival, we all sat together at a table on the dais. We had put a reclining chair for his use. A photograph of us was taken, which is there in The Religions of the World published by the Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture. In that picture you will see me sitting with Tagore and other dignitaries, including Sir Francis Younghusband, Sarojini Naidu, etc. Yet, I had to inquire of him every now and then to check how he was feeling.

The greatest draw at that meeting was Rabindranath Tagore, of whom all Indians were proud. He read out his paper while sitting in his reclining chair. It took half an hour to read the paper. It was a brilliant paper. Over 1,500 people listened to his talk in pindrop silence. Tagore was very pleased. Later he told me, ‘Swamiji, never in my life have I experienced such a calm and quiet meeting with so many people present in it. Wonderful! You’re a very good organizer.’

After reading his paper he kept on sitting; he forgot about going home. As the meeting continued, I was feeling more and more embarrassed thinking how would I face Ramananda Chatterjee if Tagore stayed at the meeting till its end. I kept on hoping and praying that Tagore would leave at least a few minutes before the meeting ended. Then Ramananda Chatterjee could be asked to preside over the rest of the meeting.

This, however, did not happen. Whenever I asked Tagore if he were tired of sitting at the meeting, he would answer, ‘Swamiji, I am feeling very well. I am enjoying everything.’ He kept on sitting and enjoying the entire proceedings of the meeting until the meeting ended, three hours after he had read out his speech. Among the speakers that day were Swami Paramananda—a disciple of Swami Vivekananda, Swami Nirvedananda, Mrs. Sarojini Naidu7 and Sir Francis Younghusband.8 Sir Francis was also in charge of giving thanks. Having heard Rabindranath Tagore’s brilliant speech, Sir Francis Younghusband said that had our Parliament of Religions been held only for that one single day, even then it would have been a great success, mainly due to the wonderful speech of Tagore!

When Tagore left at the end of the meeting, I talked to Ramananda Chatterjee and invited him to preside over a morning session of the Parliament in one of its next meetings. To my great relief, he kindly accepted the invitation.

On March 4th, the day after Tagore had presided over the meeting, both Ramananda Chatterjee and I went together to see him and inquire how he was feeling after that day’s strain of having to sit through the meeting for three more hours. But Tagore said, ‘I am feeling quite well; thank you very much. Never in my life have I attended a meeting of such absolute calmness and peacefulness. I enjoyed it thoroughly. I am also surprised at the organizing capacity of the Ramakrishna Mission. It’s really a great thing that you all have done.’ I, however, felt strongly that the success of the Centenary Celebration was not due to our own efforts. It was only the grace of Sri Ramakrishna, which made the celebration a success.

After the Centenary Celebration ended, the Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture was started in Calcutta in 1938. I made over all the residual money, publications, etc., to the Institute of Culture. Its impressive building was later constructed at a cost of more than ten million Indian rupees. This institute was an offshoot of the Centenary Celebration. Now this institute has become a famous cultural centre in Calcutta.

(Concluded.)

References

5. A kerosene lantern. At that time they did not have electric lights at the Sargachhi Ashrama.

6. Ramananda Chatterjee (1865–1943) was founder, editor and owner of the Calcutta-based magazine, The Modern Review. He is called the father of Indian journalism.

7. Sarojini Naidu or Sarojini Chattopadhyaya (1879-1949), also called Bharatiya Kokila (The Nightingale of India), was a child prodigy, freedom fighter, and poet. She was the first Indian woman to become the President of the Indian National Congress and the first woman to become the Governor of Uttar Pradesh.

8. Francis Younghusband: Lieutenant Colonel Sir Francis Edward Younghusband KCSI KCIE (1863–1942) was a British Army officer, explorer, and spiritual writer. He is remembered mainly for his travels in the Far East and Central Asia— especially the 1904 British invasion of Tibet, which he led. He was the British commissioner to Tibet and the President of the Royal Geographic Society.

Source : Vedanta Kesari, May, 2015