Whosoever knows, in the true light, My divine birth and action will not be born again when he leaves his body; he will attain Me, O Arjuna. — Gita, IV-9

In whatsoever way men approach Me, even so do I reward them; (for it is) My path, O son of Pritha, (that) men tread, in all things — Gita, IV-11

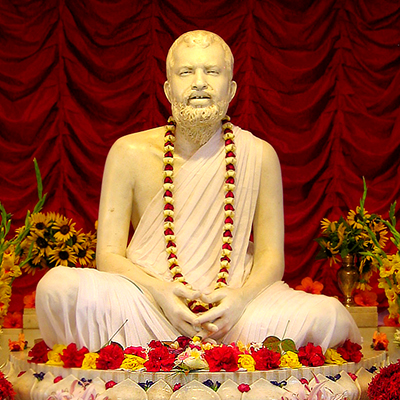

“Salutation to you, O Ramakrishna, the Reinstator of all Religions, the Embodiment of all Religions, the Great Master among all the Masters. ”

—Swami Saradananda

THE BOOK AND ITS AUTHOR

This is the first complete English version of Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga, a faithful record and exposition in Bengali of the various aspects of the life of Sri Ramakrishna (1836-86), whom the late reputed French savant Romain Rolland introduced to the Western world as “the Messiah of Bengal”. Indeed, Sri Ramakrishna’s life was a significant spiritual event of the last century. His chief disciple, Swami Vivekananda, declared, “His (Ramakrishna’s) life was a thousandfold more than his teaching, a living commentary on the texts of the Upanishads, nay, he was the spirit of the Upanishads living in human form Nowhere else in this world exists that unique perfection, that wonderful kindness for all that does not stop to justify itself, that intense sympathy for man in bondage. He lived to root out all distinction between man and woman, the rich and the poor, the literate and the illiterate, the Brahmanas and the Chandalas. . . He came to bring about the synthesis of the Eastern and Western Civilizations. Indeed, not for many a century past India produced so great, so wonderful a teacher of religious synthesis. … The new dispensation of the age is the source of great good to the whole world, specially to India; and the inspirer of this dispensation, Bhagavan Sri Ramakrishna, is the reformed and remodelled manifestation of all the past great epoch-makers in religion.” Such a life may be presented and interpreted only by a thoroughly rational mind endowed with a high order of intuitive insight and almost an encyclopaedic knowledge of the spiritual realm

Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga, the original Bengali biography of Sri Ramakrishna, based as it is on first-hand observation, assiduous collection of materials from different sources, patient sifting of evidence by way of an earnest effort for precision, and backed up by lucid interpretation of all relevant intricate problems connected with religious theories and practices, may easily be ranked as one of the best specimens of hagiographic literature.

The book was published serially in five volumes in Bengali. The first two volumes (Parts III & IV) contain illuminating discourse by way of explaining and illustrating the aspect of Sri Ramakrishna as a Guru (spiritual guide). His early days and his vigorous spiritual practices in youth are delineated in the following two volumes (Parts I & II) respectively. The last (Part V) depicts the manifestation of Divinity in and through the life of Sri Ramakrishna.

But, unfortunately, the book was incomplete. It did not cover the last few months of Sri Ramakrishna’s life. However, Romain Rolland was perfectly justified in stating, “Incomplete though the work remains, it is excellent for the subject.”

Regarding the author, the French savant cogently remarks; that he “is an authority both as a philosopher and as a historian. His books are rich in metaphysical sketches, which place the spiritual appearance of Ramakrishna exactly in its place in the rich procession of Hindu thought.” Really, the masterly treatment of the subject gives a glimpse of the marvellous capacity of the author. His wide experience, vast erudition, spirit of rational enquiry and, above all, his far-reaching spiritual achievements may be discerned even by a casual reader of the book.

An acquaintance with some details of the author’s life, may prove interesting and helpful to the readers of the present English publication of the work. It will enable them to appreciate its worth as an authentic and comprehensive record of an epoch-making spiritual phenomenon, the hallowed life of Sri Ramakrishna. Hence the following outline:

The author was Swami Saradananda, one of the outstanding monastic disciples of Sri Ramakrishna.Before he took orders his name was Sarat Chandra Chakravarty. He was born in December 1865, of a fairly well-to-do Brahmin family residing in central Calcutta.

His early life showed unmistakable signs of a saint in the making. Sedate and polite by nature, he had a robust physique, a sharp intellect and a highly sympathetic heart. Easily the best boy of his class, Sarat Chandra made his mark also in the debating society of his school, though it was not possible for him to hurt anybody’s feelings by a harsh word or a caustic taunt. His loving heart invariably prompted him to serve any ailing acquaintance, be he a relative, a friend, a neighbour or a menial,—and this even if the disease was an infectious one. To crown all, a remarkable feature of Sarat Chandra’s mental make-up was its precocious bias for religion. Even as a little boy he evinced an instinctive craving for religious rites. Mimic worship was the child’s favourite play. As he grew up, this play gradually turned into the most serious pursuit of his life.

Born of an orthodox Brahmin family, he inherited a profound reverence for the traditional Hindu religion. Towards the end of his school-days his faith was fairly secured on rational grounds as he came in touch with a sophisticated form of Hinduism through the New Dispensation Movement of the Brahmo Samaj. His ardour for spiritual growth got a fresh stimulus when in St. Xavier’s College he contacted the Holy Bible and became inspired by the life and teachings of Jesus. Lastly, it was during his college-days that he lighted upon an exalted spiritual guide who resolved all his possible doubts regarding the truth behind all religions, and by whose surging spiritual power the course of Sarat Chandra’s life was entirely changed.

The spiritual guide was Sri Ramakrishna, then known as the Saint of Dakshineswar, a northern suburb of Calcutta. The news of a towering spiritual personality residing in a Kali temple in that suburb had been spreading for some years among the Calcutta public through several Calcutta journals, particularly under the auspices of the Brahmo Samaj. This was drawing a stream of pious visitors, young and old, from Calcutta to meet the saint. Sarat Chandra and his cousin Sasi (later Swami Ramakrishnananda) were caught in the current. Both of them were then college students and were in their teens when one day in October 1883, they went over to pay their respects to the saint.

Sri Ramakrishna appeared to be waiting for such pious young souls. As soon as he met them, he hailed them with delight and made them his own by his endearing and edifying talks. By his sweet and simple words he burnt deep into their minds the supreme need of renouncing sense-enjoyments for realizing God. They felt instinctively that in Sri Ramakrishna they had found a worthy guide on the spiritual path.

After this first visit Sarat Chandra made it a point to come alone to meet the saint every Thursday, which was a holiday in his college. The enchantment of Sri Ramakrishna’s incomparably pure and selfless love was upon him, and as days went on, he began to feel an irresistible attraction towards the holy man. Through repeated contact with him Sarat Chandra’s ideas about practical religion became clearer and clearer, and he advanced step by step on the spiritual path as directed by Sri Ramakrishna.

Even in his early youth, Sarat Chandra’s spiritual aspirations were pitched very high. He was not after washy sentiments, nor even after visions. God in any particular form was not his quest. He wanted to see Him manifested in all creatures. Though told by Sri Ramakrishna that this was the finale of spiritual attainment and could not be easily achieved, Sarat Chandra said that nothing else could satisfy him, and that he was determined to get to that blessed state, whatever difficulties might stand in the way. Evidently Sri Ramakrishna was pleased to find such a prodigious mental calibre in the young aspirant, and suggested that the latter should make friends with Narendranath (later Swami Vivekananda), a potential spiritual giant.

Within a year of his first visit to the saint, Sarat Chandra came to be attached to Narendranath by a bond of intimate friendship. One day in October 1884, hearing from Narendranath about his marvellous mystic experiences connected with Sri Ramakrishna, Sarat Chandra’s perspective of the Saint of Dakshineswar became radically changed. He perceived that Sri Ramakrishna was not merely a saint but a spiritual personage ranking with the Prophets and Incarnations he had heard about.

Naturally, after the above incident, Sarat Chandra’s love and esteem for Sri Ramakrishna soared to spontaneous adoration of Divinity in the garb of the holy man. With unquestioned faith he resigned himself to the loving care and guidance of the saint as his Guru, and devoted himself heart and soul to spiritual practice, as far as the limits of his home environment and academic career would allow. Sri Ramakrishna, on his part, recognizing in Sarat an aspiring soul of a very high order with a brilliant past, poured out his unstinted grace upon the young disciple and vitalized his budding spiritual genius.

Things went on smoothly till the middle of the year 1885, when Sri Ramakrishna was laid up with a serious attack of throat trouble (cancer) and was brought to a rented house in the quarter of Calcutta for treatment. The alarming news came to Sarat Chandra like a bolt from the blue. The terrible shock he received, however, served eventually as a fillip to his spiritual progress. The moorings of worldly life seemed immediately to give way. With anxious concern for the health of his beloved Guru, he rushed to his bed-side, playing truant from his home and bidding adieu to the Calcutta Medical College, which he had recently joined. Shortly, he began to live day and night with Sri Ramakrishna, and followed him when after about four months he was removed to a garden house in Kasipur, a northern suburb of Calcutta. With his phenomenal zeal for nursing, Sarat Chandra kept on tending the Master till the last moment of the latter’s earthly life.

Sri Ramakrishna’s illness lasting for about a year proved to be a signal, as it were, for his picked, young disciples to tear themselves away from their home life and be eventually banded together into an incipient holy brotherhood under their preeminent leader Narendranath. They came obviously to nurse their beloved Guru, but stayed on to be drilled into monastic life. It was in the Kasipur garden house that one day Sarat Chandra with most of his comrades received from Sri Ramakrishna the ochre cloth, the distinct garb of a Hindu monk. It was here that, under the Master’s instructions and encouragement, they learnt to beg their food like Sannyasins in order to practise complete resignation to Providence as well as to purge their minds of deep-rooted egotistic tendencies. Thus inspired by their Guru with the highest spiritual ideals, and ushered symbolically into monasticism, they forgot all other concerns except the service of their beloved Master and an intense devotion to spiritual practice.

In this way the lofty aim of realizing God was rooted deeply in their minds. The world and its humdrum affairs had no attraction for them. And this state of their minds became more intense after the Master passed away in August 1886. Soon after that, a monastery was started for them in a rented house at Baranagar, not far from the Kasipur garden house. Though for a time Sarat Chandra returned home reluctantly, yet as soon as the monastery was started, he began to visit it off and on and spend long hours in the company of his comrades, absorbed in spiritual practice or in talks about the life and teachings of the Master. Apprehending that his eldest son Sarat was tending to be a recluse, and failing to turn his mind towards worldly life by arguments; Sarat’s father, Girish Chandra, took the extreme step of cutting off all contacts of his son with his fellow disciples by locking him up in a room. Unruffled, Sarat Chandra accepted the unenviable solitary confinement in his own house, and fully utilized his loneliness in focussing his mind on his spiritual objective. However, one day when one of his sympathetic younger brothers furtively unlocked the room, Sarat Chandra silently walked out of the house and went straight to the Baranagar monastery. Shortly after this, he and some of his brother disciples assembled in the village home of Baburam (later Swami Premananda), and there, inspired by their leader Narendranath’s exhortation during a night-long vigil round a sacred fire, they took the solemn vow of Sannyasa, that is, monasticism for life.

Thus, step by step and without any fuss, Sarat Chandra forged ahead on the path chalked out for Hindu monks. A period of austere monastic life in the Baranagar monastery followed. Without paying any heed to the meagre allowance of food and dress that the slender resources of the monastery provided for these educated middle-class youths, they braced themselves up for the arduous task of realizing the Divine. No other concern could stand in the way of their one-pointed spiritual endeavour. Meditation, hymns, prayers, scriptural study and discussion on religious topics were all that absorbed most of their time and energy.

Thus the young spiritual aspirants kept themselves busy and were not in a mood to rest before they reached their goal. On one auspicious day in the Baranagar monastery, they performed the prescribed sacred rite known as Viraja Homa and thus ceremonially joined the traditional Hindu monastic order. Though their monastic life was virtually started by Sri Ramakrishna during his last days in the Kasipur garden house, and was reinforced by their solemn vows in the village home of Baburam under the inspiration of Narendranath, it was from this day that they commenced a new life as sanctioned by Hindu religious texts. Wiping out all previous impressions about their castes and social positions related to the families of their birth, they discarded even their previous names and titles. From this day Sarat Chandra came to be known as Swami Saradananda.

Soon, however, Saradananda, like most of the inmates of the Baranagar monastery, was seized by a passion for leading the lonely life of a wandering monk (Parivrajaka). Even the company of his brothers as well as the comparatively secure life within the monastery sat on his nerves as an unbearable bondage. He felt an indomitable urge for moving about from place to place as an unfettered soul in pursuit of his spiritual aim, depending absolutely on God for food and shelter. Sacred cities, river banks and Himalayan retreats, rich with spiritual associations piled up by saints and sages through scores of centuries, made their irresistible appeal to his pure mind.

His first sojourn outside the Baranagar monastery was at Puri, the sea-side holy city of Jagannath. After a time he came back, and went out again to spend a considerable time in various sacred places in Northern India. Through Banaras and Ayodhya he proceeded to Hrishikesh, where, absorbed in spiritual practice, he stayed on for some months leading the traditional life of Hindu monks. In the summer of 1890, he climbed up the Himalayas to visit Kedarnath, Tunganath and Badrinarayan, and in July came down to Almora, where within a month he met Swami Vivekananda. With the latter he went again to Hrishikesh through the Garhwal State. Then, after spending some time in Meerut and Delhi with Swami Vivekananda, he went down to Banaras, visiting on the way holy places like Mathura, Vrindavan and Prayag (Allahabad). After another period of intense spiritual practice in the holy city of Banaras, he had an attack of blood dysentery, which eventually brought him back to the Baranagar monastery in September 1891. On recovery, he went to Jayramvati to pay his respects to the spiritual consort of Sri Ramakrishna, known to the devotees as the Holy Mother.

The itinerary of a wandering monk like Swami Saradananda may be followed in detail, but the path traversed by his mind speeding through spiritual experiences cannot be mapped. How, when and by what stages his spiritual genius unfolded itself completely, cannot be traced. Thus the most interesting and substantial contents of his life remained like a sealed book in the bosom of the sage.

In 1892 the monastery was shifted from Baranagar to Alambazar, a place nearer to the Dakshineswar temple. For a fairly long time before and after that, the brotherhood had no knowledge of the whereabouts of their leader Narendranath, till they were thrilled to learn that their itinerant brother had crossed the seas and burst upon the American society in the wake of the Chicago Parliament of Religions as Swami Vivekananda, the Cyclonic Monk of India. From March 1894, the latter kept himself in touch with the brotherhood of the Alambazar monastery through regular correspondence, and went on inspiring it to step out of the traditional monastic seclusion and to inaugurate a new Order of Hindu monks accepting as its motto individual salvation together with the service of deified humanity. Two years later he called Swami Saradananda to assist him in his Vedanta movement in the West. Accordingly, on the first of April 1896, Swami Saradananda reached London, where about a month later Swami Vivekananda arrived for the second time from America.

After delivering a few discourses in London, Swami Saradananda had to go over to the United States and join the Vedanta Society that had already been established by Swami Vivekananda in New York. There he set about doing some solid work through his interesting lectures on the Vedanta and the ideas and ideals of the Hindus as well as through his edifying classes on the Yoga System He made precious contributions to the Greenacre Conference of Comparative Religions, the Brooklyn Ethical Association and to the interested elite of Boston and New York by way of introducing the Hindu view of life to the American public. His talks coming out of the fullness of the heart had a marked effect on the audience. Besides, his calm, dignified and courteous bearing, his catholic outlook and universal love won for him many friends and admirers over there. Under his vigilant care the Vedanta Society in New York was being placed on a sound footing, when a call from the leader made him cut short his work in the West and sail for India via Europe on the 12th of January, 1898.

Swami Vivekananda, the leader, had come back to India in January 1897, and in the midst of a hectic period of broadcasting his message practically all over India, from Colombo to Almora, he had started working breathlessly at the foundation of the Ramakrishna Order of monks and the Ramakrishna Mission. On the first of May of the same year, he inaugurated the Ramakrishna Mission, an Association of lay and monastic members for carrying on spiritual and humanitarian work. Within a year after his arrival, the monastery at Alambazar was shifted temporarily to Nilambar Mukherjee’s garden house at Belur, where close by, on the western bank of the Ganga, a suitable site was purchased for building up a permanent monastery for the brotherhood; At this stage Swami Saradananda’s service was requisitioned for piloting the Ramakrishna Mission as its Secretary as well as for organizing the management of the monastery.

Swami Saradananda reached the monastery in the above garden house early in February 1898 and took up the responsible duties allotted to him. At the beginning of the next year the monastery was shifted to its permanent site now known as the Belur Math, and within a couple of years after that Swami Vivekananda placed the monastic organization on a stable legal basis by executing a Trust-Deed and incorporating in that organization the ideas, ideals and activities for which the Ramakrishna Mission Association had been started. In this new set-up also Swami Saradananda was chosen by the leader to function as its Secretary. It may be mentioned that later on, when for certain practical considerations the Ramakrishna Math and Mission were split up into two parallel organizations, the Swami continued to direct the affairs of both of them as their Secretary. With the allegiance of a faithful follower, Swami Saradananda stuck to this post right up to the end of his life, considering it to be a sacred task entrusted to him by Swami Vivekananda.

However, Swami Saradananda, equipped with his fresh experience of the Western methods of organization, quickly brought the internal affairs of the monastery into perfect order. Under his care and guidance, a routine life divided between spiritual practice, scriptural study and household jobs went on like clock-work within the monastery. Moreover, with his knowledge of the needs and temperaments of the Western people, he applied himself in right earnest to training up preachers for the West from among the deserving young monks.

On the top of these, he had to attend to quite a number of occasional duties at the instance of the leader. Within a few months of his arrival from America, he had to take an active part in conducting the Ramakrishna Mission plague relief work in Calcutta; several months later he had to act as a guide for some Western disciples of Swami Vivekananda in their tour through a number of historical sites in Northern India. Early next year, shortly after the monastery had been shifted to its permanent site, he had to engage himself in collecting funds for the Belur Math in the course of a lecturing tour through some of the important States in Rajasthan and Sourashtra in Northwestern India. Coming back to the Math shortly before Swami Vivekananda left for his second visit to the West, he devoted himself with his usual zeal to his normal duties within the monastery. Towards the end of the year he visited some important towns in Eastern Bengal, and roused the spiritual fervour of the interested people in those parts by his inspiring talks and instructions.

Swami Vivekananda returned from his second tour in the West towards the end of 1900; he executed the Belur Math Trust-Deed in January 1901; and in July 1902 he passed away, leaving the Ramakrishna Math and Mission to the care of the Trustees, of whom Swami Brahmananda and Swami Saradananda held the pivotal positions of the President and the Secretary respectively. In spite of the severe shock of separation from their beloved and esteemed leader, Swami Saradananda proceeded to shoulder the onerous responsibility of the day-to-day administration of the Math and Mission under the inspired guidance of the President Swami Brahmananda, the spiritual child of Sri Ramakrishna.

Shortly, Swami Saradananda took upon himself the additional task of running and editing the Bengali monthly magazine, Udbodhan, that had been started about three years back under the direction of Swami Vivekananda and was being ably conducted by one of his brilliant colleagues, Swami Trigunatitananda. As the latter had to leave India for joining one of the preaching centres of the Mission in the United States, the magazine was about to stop for want of a capable organizer, when Swami Saradananda stepped in. Under his efficient and persevering care the Udbodhan went on gaining in popularity, as had been desired by the departed leader, and its financial condition gradually looked up. After several years of keen struggle and hard work it became possible for the Swami to move the Udbodhan Office to a permanent house of its own.

It was to find a permanent Calcutta residence for the Holy Mother that the Swami felt the urge of getting up the building as quickly as possible, even by incurring a loan on his own responsibility. The upper storey of the house was reserved for her Residence when she would come to stay in Calcutta in order to bless the monks and novitiates of the Ramakrishna Order as well as hundreds of devotees from far and near. She graced this house by her first visit on May 23, 1909. Of course, the additional purpose of the house was to accommodate the office of the Udbodhan, which was fast developing into a publication concern mainly of Bengali books comprising mostly of what is known as Ramakrishna-Vivekananda literature. The ground-floor was set apart for this. This is why even to this day the house is known to the devotees as the Mother’s house, and to the general public as the Udbodhan Office.

However, it was to pay off this loan that Swami Saradananda hit upon the idea of writing and publishing an authentic biography of Sri Ramakrishna. With supreme enthusiasm he bent himself to see through the work, sharing all the time the ever-increasing burden of directing the affairs of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission. He vigorously applied himself to collecting all available data and sifting them with scrupulous care in order to bring out a correct account of the Master’s life, as far as that was possible, relying on nothing but indubitable evidences. Day in, day out, year afer year, the Swami would remain absorbed in this work before a tiny writing desk in a small room, though distracted now and then by visitors or by pressing duties in connection with the Math and Mission. This was the genesis of the brilliant Bengali production, Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga, that came out first serially as articles in the Udbodhan since 1909 and then in five volumes between the years 1911 and 1918.

In 1909 the Ramakrishna Mission was organized as a separate body for carrying on philanthropic and educational activities among all sections of people, irrespective of caste, creed or colour. Branch centres of the Ramakrishna Mission as well as those of the Ramakrishna Math were opened one afer another in different parts of India and in certain foreign lands, and these went on multiplying as years rolled on. Besides, occasional relief works during wide-spread calamities due to floods, famines, earthquakes or epidemics in this country had to be organized and conducted from time to time. Naturally, the task of piloting all these as the Secretary of both the Math and the Mission became more and more arduous as years went by. Yet Swami Saradananda was always found equal to the occasion. With his usual calmness he would silently and unostentatiously direct the affairs, meeting embarrassing situations sometimes and solving many a complicated problem arising out of them. It was through his bold and sagacious handling that a number of political inspects aspiring for spiritual life could join the Ramakrishna Order and put in valuable work unmolested by the Government. When the political authorities looked askance at even social service organizations, it was through his efforts that the Ramakrishna Mission could carry on its activities unhampered by any governmental measure.

Beneath the intense and multifarious activities of Swami Saradananda, one may perceive the supernormal lineaments of his inner life. It is through a seer’s responses to the world outside that one may possibly get a clue to the source of his inspiration and energy. The following incidents of Swami Saradananda’s life obviously give such a clue.

Towards the end of 1898, while he was travelling in a tonga from Rawalpindi to Srinagar in Kashmir in order to meet Swami Vivekananda and his party, he gave a convincing proof of his marvellous equanimity in the face of a perilous situation. It so happened that all of a sudden the horse took fright and crazily rushed downhill with the vehicle at a breakneck speed. Luckily, its mad career was arrested some way down by a big tree standing on the sloping hill-side, when Swami Saradananda quietly came out of the carriage. At that very moment a heavy boulder crashed down from above and, sparing his person by a few inches, fell upon the horse and killed it on the spot. Absolutely calm all through the incident that might very well have cost his life, the Swami remained a disinterested witness of the entire scene like a true Sthitaprajna, one whose consciousness is anchored in the higher Self.

The extraordinary quietude of a liberated soul before a precarious situation was also demonstrated through some other thrilling incidents of his life. On his voyage to London in 1896, when his ship was overtaken by a cyclone in the Mediterranean, the Swami sat unmoved, witnessing dispassionately the panicky stampede and desperate cries all about him On another occasion, later in life, while crossing the Ganga in a country boat that was about to be capsized by a violent storm, the Swami sat unperturbed, as if there was nothing serious about him to take notice of. His absolutely unconcerned attitude went so far as to impel his panicky companion to make a rude gesture. Such behaviour of the dismayed companion drew only a genial smile from the Swami.

Another incident of a different nature has a peculiar significance, reminding one of Sri Ramakrishna’s vision of Swami Saradananda’s previous life as a companion (apostle) of Jesus. On his way to London from India, when he visited St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, his mind was abruptly whisked off to a super-conscious plane, and he fell into a deep mystic trance (Samadhi). What he actually saw and felt at that time remained a closely guarded secret of his life. One may reasonably guess, however, that the holy Cathedral associated with the sacred memory of the apostles of Jesus stirred up a vivid recollection of his previous life as had been visualized by the Master, and drowned for the time being his consciousness of his immediate surroundings.

Swami Saradananda’s spiritual eminence read through these significant incidents of his life was verified by a few hints given by him on some rare occasions. On the pages of his personal diary one finds repeated mention of his direct communion with the Divine Mother. Then his following explicit admission while dedicating his illuminating Bengali book Bharate Shakti-Puja (Worship of the Divine Mother in India) may be cited as another instance to the point: “The book is dedicated with great devotion to those by whose grace the author has been blessed with the realization of the Divine Mother in every woman on earth.” This shows to what a peak of spiritual experience his mind had been lifted. Indeed, such a realization is the very goal of Mother Worship (Tantrika Sadhana). Incidentally it may be mentioned that Swami Saradananda went through a course of this kind of spiritual practice within about a couple of years after his return from the West. Later in life, in answer to the repeated and earnest queries of a monastic attendant regarding Swami Saradananda’s spiritual attainment, a significant hint escaped unawares from the Swami’s usually tight lips: “Nothing beyond my spiritual experience has been recorded in the book, Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga. ” And this book is replete with spiritual realizations of various kinds, including the highest one of transcendental oneness in Nirvikalpa Samadhi. This hint sums up the core of his inner life as that of a liberated soul—a seer of the ultimate verities of life and existence.

However, over and above all other activities of Swami Saradananda connected with the Math and the Mission as well as with the composition and publication of his Master’s biography, his primary concern appeared to be looking after the ease, convenience and health of the Holy Mother. He regarded her as the Divine Mother incarnate and placed himself completely at her service. Whether she stayed in her rural home at Jayramvati or in the city, the Swami was all attention to her. The Calcutta house was erected, as we have seen, mainly for facilitating her comfortable sojourn in the city. And for doing this as quickly as possible, he did not mind running into debt; nor did he mind undergoing strenuous labour for about nine years at a stretch in the production and publication of Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila- prasanga in order to clear off that debt. Indeed, his devotion to the Holy Mother cannot be fathomed. Seated in a small room downstairs in the Calcutta house, he would be found regulating the stream of her visitors exactly like her door keeper. Sometimes he would sportively introduce himself to strangers as the Mother’s janitor. One could learn from his bearing that it was a glory and privilege to be allowed to serve the Holy Mother even in this way. Throughout her last stay in the Calcutta house during her fatal illness in 1920, with what anxious care the Swami would go into minute details regarding her medical treatment and nursing, sparing no pains, though in vain, for bringing her round!

Three years later in April 1923, the Swami had the satisfaction of perpetuating the sacred memory of the Holy Mother by getting a temple erected and dedicated to her in her native village Jayramvati. During the dedication ceremony, the benignant mood of the Holy Mother seemed to possess the Swami’s mind as he went on like her, gracing with spiritual initiation all sorts of people who approached him on that occasion. One could feel the spiritual fervour radiated by the Swami on the festive days connected with the ceremony.

The dedication of the Holy Mother’s temple was perhaps the final oblation offered by Swami Saradananda by way of completing his life-work, which was one long-continued sacrificial rite. After the successive exits of some of the stalwarts of the brotherhood, the passing away of the Holy Mother in July 1920, followed within two years by that of Swami Brahmananda, the first Abbot and inspired guide of the Order, shook even the unmoved Swami. These bereavements appeared to squeeze out the Swami’s zest for work. That was why after seeing through the construction and dedication of the Holy Mother’s temple, the Swami practically detached himself from active work and went on spending long hours in meditation. He gave up writing and was never in a mood even to finish his magnum opus, Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga.

The only thing that concerned him at the moment was to instil into the junior members of the Order unflinching faith in the ideas and ideals left by its founder, Swami Vivekananda, and also to train up a batch of young monks for sharing the burden of piloting the organization that he had been carrying on his own shoulders. For this purpose, in 1926, he called a Convention of representatives from all Math and Mission centres; he surveyed before them, through his inaugural address, the origin and growth of the Ramakrishna movement that was careering at the time at top speed, cautioned them against the possible pitfalls on the path ahead and exhorted them emphatically to stand firmly by the ideals, so that they might march onward clearing all hurdles in the way. In the wake of this Convention, the Swami set up a Working Committee for advising the Secretary of the Math and the Mission on practically all administrative problems. As the remaining elders were about to disappear from the stage, it was in the fitness of things that a fresh batch of junior monks should be trained for stepping into their shoes. This device of the Working Committee inaugurated by Swami Saradananda served not only the purpose for the time being but also has proved to be a permanent and useful administrative link of the Math and Mission;

Thus enthusing the young members of the Order by holding aloft the ideas and ideals they were to strive after, and devising ways and means for realizing them in practice through successive generations, Swami Saradananda complacently laid down the charge entrusted to him some three decades back by his beloved leader Swami Vivekananda, and placidly entered Mahasamadhi on August 19, 1927.

An illumined soul, freed completely from all kinds of bondage, is not restricted by any prescribed code of life. Even the idea of duty ceases to have any meaning to him who has seen through the universe and realized the all-pervading Oneness as its essence. Yet such a liberated soul, when commissioned by the Divine Will to work for the uplift of humanity, does display distinctive traits of character befitting the role he is made to play. Swami Saradananda’s role was to demonstrate through his life the pattern of an ideal Karma-yogi. With perfect non-attachment and self-possession he would go on scrupulously discharging the duties before him, paying equal attention to the minor as to the major ones. Neither frown nor favour, nor any number of difficulties could swerve him from the straight and strict path.

Indeed, he held up the model of an ideal worker as desired by Swami Vivekananda. His rational mind, compassionate heart, pure and perfectly poised mind, indomitable energy and rare organizing ability combined to set up such a model. “Infinite patience, infinite purity, and infinite perseverance,” as Swami Vivekananda wanted to see, were in his blood. The latter once remarked, “Sarat’s blood is as cold as that of a fish, nothing can inflame it.” His heart was “deep as the ocean, broad as the infinite sky,” as Swami Vivekananda would have it. Swami Saradananda saw potential divinity even in the worst sinner, and tried to the last to work it up with extreme love and sympathy. Truculent and refractory persons thrown over by his colleagues found refuge under his benign care, and they naturally gathered round him Indeed, he was a living illustration of the truth of Swami Vivekananda’s assertion, “The man of renunciation sees all with an equal eye, and devotes himself to the service of all.” Without any air of superiority, he treated all people alike with love and tenderness. He never cared for his personal ease and comfort. He would hardly accept any corporal service even from his own disciples. But he was ever ready to face any amount of hardship or even to hazard his life for helping others out of danger. While crossing a ravine on the Himalayas on his way to the Badrinarayan temple, he handed over his stick to one of the fellow pilgrims, an unknown old woman, without thinking for a moment what a risky adventure it would be for him to get over the steep hillside without a staff in his hand for support. He would be found by the bed-side of patients suffering from contagious fatal diseases, whom their own kith and kin would not dare contact. His solacing words would give relief to many a person aching with mental agonies.

A distinctive mark of personality was stamped on his general demeanour. It was an object-lesson on decorum. Even those who were punctilious about etiquette would be captivated by his winning manners. The patience he would usually exhibit while listening to and answering even silly questions from youngsters was surely marvellous. His sweet and soothing voice would often take the edge off any harsh word that he might have to utter by way of rebuking an offender. It would sound like a mother’s appeal to her erring child. Yet this motherly voice was balanced by an awe-inspiring solemnity, and these combined effectively to produce the desired effect on the conscience of the guilty.

Swami Saradananda was an exemplar of methodical work. Slow, steady and regular in his movements, he would regard even a trifle with as much serious attention as it deserved. Any undertaking, big or small, was equally sacred to his thorough-going mind as an act of worship.

Always cool in judgment, he was hardly found to rush to any decision on insufficient or unreliable data before him He was perfectly rational, considerate and psychological in his methods while dealing with men and their affairs.

Lastly, love for orderliness was an innate virtue with him Though quite simple in his requirements, he would scrupulously see that everything about him was kept neat and tidy. Possibly, this trait was reinforced by the example of his Master, Sri Ramakrishna, who had been a past master in simplicity with orderliness.

From the above sketch one may get an idea of the part that the author of Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lila-prasanga, Swami Saradananda, had to play as one of the prime organizers of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission. It will ever remain a perfect model to be emulated by all who will seek personal salvation along with the well-being of the world as their aim of life.

SWAMI NIRVEDANANDA