Swami Vivekananda composed the mantra,

Sthapakaya cha dharmasya sarvadharmasvarupine

Avataravarishthaya ramakrishnaya te namah

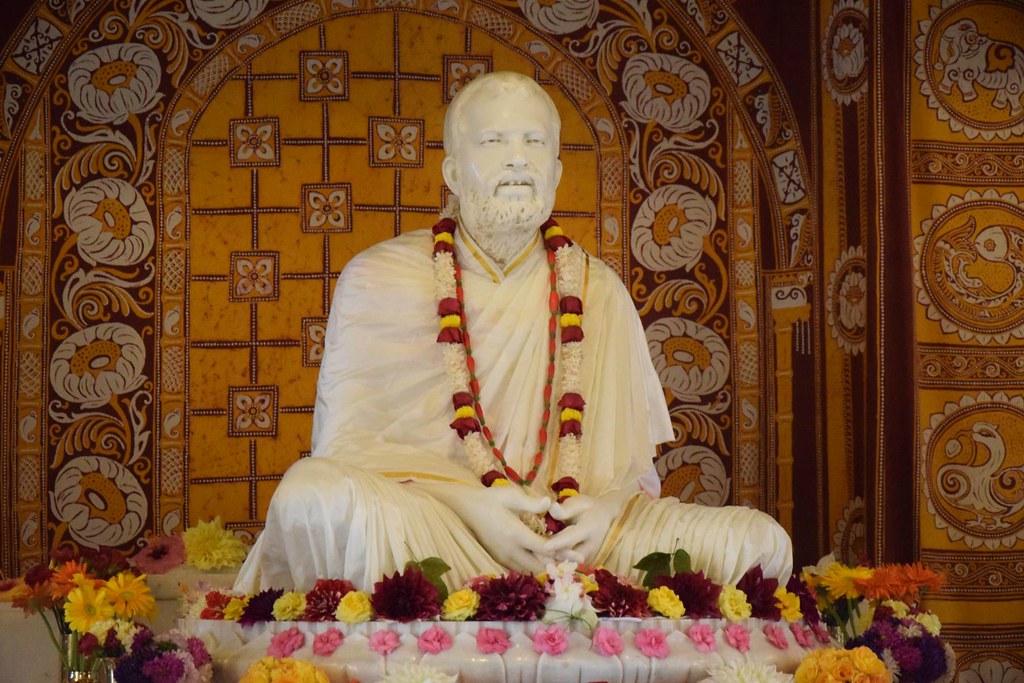

in which he described Sri Ramakrishna as the foremost of divine incarnations. Swamiji was eminently qualified to make this assessment of Sri Ramakrishna’s spiritual greatness. It is extremely difficult to make such an evaluation unless one also possesses, at least to some degree, an insight into the world of the Spirit, into the realm of mystical experience and superconscious awareness. Sri Ramakrishna used to say that it was extremely difficult to recognize an incarnation, citing as an example that only twelve rishis could recognize Ramachandra. He gave an illustration of a servant who was given a diamond by his master to take to the market to assess its value. The servant took it to an eggplant seller, who offered him nine seers of eggplants for it. Then to a cloth dealer, who said he would give nine hundred rupees for the diamond. Finally, his master sent him to a jeweler who, just by glancing at the diamond, immediately recognized its value saying, ‘I will give you one hundred thousand rupees for it.’

Swami Saradananda, the author of Sri Sri Ramakrishna Lilaprasanga or The Great Master and Mahendra Nath Gupta, known as M., the complier of the Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita, The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, are two such jewelers who not only recognized who Sri Ramakrishna was, but who have, in turn, opened the door for spiritual seekers to enter into the life of one who was completely immersed in God-consciousness. They are truly the Master’s Vyasas—the revered divine compiler and author of Hindu tradition. Without these two works, we would not have the all-encompassing picture of Sri Ramakrishna that we have today. Sri Ramakrishna used to say that his divinity was concealed that:

A band of minstrels suddenly appears, dances, and sings, and it departs in the same manner. They come and they return, but none recognizes them.

Sri Ramakrishna came and went with his band of minstrels, but fortunately before the troupe exited the stage, the performance was recorded. Otherwise, who would have believed that such a God-intoxicated person really existed, that such an extraordinary divine play was enacted just the other day?

1

The Great Master is a biography of Sri Ramakrishna. However, it is not a typical chronological biography, but rather a comprehensive, analytical account of the Master’s life and sadhana. It may be considered primary source material; it’s authoritative, based on firsthand evidence and the recollection of people who knew Sri Ramakrishna, including Sri Sarada Devi, the Holy Mother, many of his direct disciples and others, as well as what the Master said about himself. Sri Ramakrishna never taught anything to anyone that he himself had not realized. There is another outstanding, singular feature of this account: It is written not only by a direct monastic disciple and a knower of God, but by one who said he had not written about anything that he had not personally experienced. This fact alone is extraordinary, giving this biography a unique status among all the available information about the Master. We cannot find such a claim in any other book about Sri Ramakrishna.

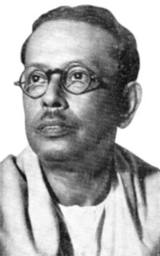

Initially, Swami Saradananda began writing The Great Master* as a way to raise money for Holy Mother’s Udbodhan house in Calcutta. He began his narration with a discussion on Sri Ramakrishna as a spiritual teacher, which eventually formed the third part of the book, and not from his birth then going forward as one finds in most biographies. Further, it does not cover the entire story of the Master’s life. Some people contend that the swami never intended to write a complete biography and therefore it was not composed in a chronological order. Apparently, the swami focused his attention primarily on establishing a consolidating principle that would bring together all the known facts of Sri Ramakrishna’s life. Therefore, he centered his analysis round the concept of the Master’s state of bhavamukha (dwelling midway between relative and absolute consciousness) as a way of explaining the significance of his life and message. This is an unparalleled approach how Sri Ramakrishna lived his life, practiced sadhana, taught and trained his disciples. This is perhaps the greatest contribution The Great Master has made in disclosing the relevance of the Master’s life and teachings by putting them in context with his exalted spiritual state.

Formally, The Great Master begins with his family background, the various spiritual experiences of his mother prior to his birth, and then in chapter five his actual birth in 1836, concluding with his stay at Shyampukur in Calcutta (Kolkata) for his cancer treatment. Swami Saradananda passed away before the book was completed. Other material was added later. Although incomplete in one sense, The Great Master is much more than a conventional biography.

Sri Ramakrishna was scientific in his practice of religion. Swami Saradananda stresses this aspect, which, in spite of the Master’s parochial surroundings, is quite modern in content. His emphasis was on rational inquiry, observation, experimentation, and direct experience. According to Sri Ramakrishna, religion is realization. In addition, Swami Saradananda set the stage, so to speak, for Sri Ramakrishna’s life and message by examining current social customs of his times, the educational system, the religious teachers and sects of the 19th century, mysticism, and philosophy. Certainly it can be said that he lived his life at the crossroads where various religious traditions of India met. Sri Ramakrishna was able to reach out to all sadhakas from various faith traditions on his or her path. His insights into the world of the Spirit were unfathomable.

The Great Master clearly demonstrates how his life was literally a synthesis, a bridge connecting all religions, because his experience verified that every religion is equally true and valid. Sri Ramakrishna reiterated the ancient statement of the Rig Veda: ‘Truth is one; sages call it by various names.’ It has been said: ‘Sri Ramakrishna’s life was his message. His biography is therefore an extremely important piece of literature, and the philosophy of the Ramakrishna Movement is based upon it.’

2

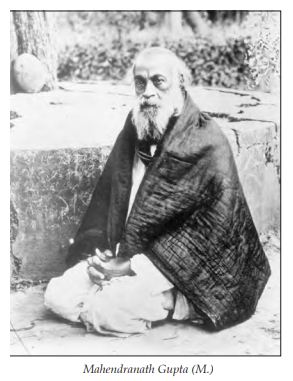

The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, on the other hand, is a unique account of Sri Ramakrishna’s life spanning a four-year period, 1882-1886, while he was living in the Dakshineswar temple garden. Recorded in a personal diary, M.’s eye witness account of the intimate details of the Master’s daily life and conversations provide a rare insight into the Master’s sublime spiritual state and his direct experience of superconscious divine moods.

M., well-educated and a highly intelligent competent reporter, was skilled in portraying visual images through words. His unusual literary genius transports the reader, as it were, to the temple garden where Sri Ramakrishna’s divine play was being enacted and which M. was observing closely. The entire drama: Sri Ramakrishna’s exalted states, all those who were with him, the scenes depicting the temple compound, with its various temples and gardens with the Ganga flowing nearby, vividly come to life. Thus M. has provided an unprecedented opportunity to have the Master’s holy company in real time.

Sri Ramakrishna, knowing the future value of M.’s diary, encouraged M. to note down his words and would ask him to repeat instructions and conversations to make sure that he had recorded them accurately. If necessary, he would correct or clarify his teachings. Even with the limitations of language, M. was able to convey some idea of the Master’s deep mystical realizations. He also captured the Master’s straightforward thoughts through his original, charming utterances. The Master always used common everyday examples and illustrations to convey the highest truths. Everything about him was simple and pure; M. captured this childlike innocence throughout his diary. The teachings found in the Gospel are invaluable practical instructions for living a spiritual life with the goal, ‘God can be seen’.

As a close disciple, astute observer, endowed with an almost photographic memory, M.’s account is also considered an authoritative, primary source, not secondary source material. Further, the Gospel is based on firsthand evidence and the keen memory of one who knew him intimately as well. M. was present during all the conversations recorded in the Gospel. His words genuinely represent the universality of Sri Ramakrishna’s spiritual greatness.

M. was not interested in writing a biography, but in merely keeping a diary for his recollection and personal sadhana. Later, after Sri Ramakrishna’s death, Holy Mother convinced M. to publish his diary. He had no intention of doing this previously. When he did publish it, he did so here and there in various journals, not originally as a book. The first of five published volumes of conversations in Bengali was in 1897 and the last in 1932. Later, the Madras Math selected certain chapters and published a two-volume English translation. Swami Nikhilananda later translated the Bengali into English and published a single volume in 1942.

Although The Great Master and the Gospel are two entirely different accounts of Sri Ramakrishna, they were written with diverse motives and approaches, by two disciples, a monk and a householder, under completely different circumstances; they are actually complementary to our understanding of the profound, vastly comprehensive life and spiritual experiences of, as Swami Vivekananda declared, the greatest spiritual teacher of all times.

(To be continued. . .)

Behind this mind of ours there is a subtle, spiritual mind, existing in seed-form. Through the practice of contemplating, prayer, and japam, this mind is developed, and with this development a new vision opens up and the aspirant realizes many spiritual truths. This, however, is not the final experience. The subtle mind leads the aspirant nearer to God, but it cannot reach God, the supreme Atman.

—Swami Brahmananda

Source : Vedanta Kesari, April, 2016