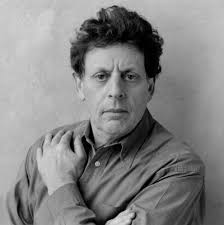

Philip Glass has had an extraordinary and unprecedented impact upon the musical and intellectual life of his time. The operas—‘Einstein on the Beach’, ‘Satyagraha’, ‘Akhnaten’ and ‘The Voyage’ among others—play throughout the world’s leading houses, and rarely to an empty seat. Born in Baltimore, he began his musical studies at the age of eight. Glass has always gone his own way.

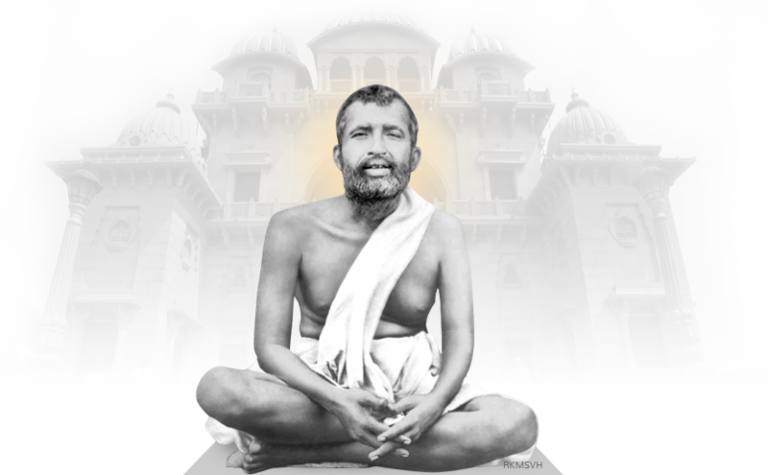

Sri Ramakrishna was born on February 18, 1836 in Kamarpukur, a village in rural Bengal. As a young man he took up service in the temple dedicated to Kali, The Divine Mother, at Dakshineshwar, a village about ten miles north of Calcutta in those years. There he remained for the rest of his life, dying in the early hours of Monday, August 16, 1886. The Kali temple at Dakshineshwar is still there today, but is now surrounded by an ever-expanding and bustling Calcutta. By coincidence, it stands not far from the place established for the work and residence of the late Mother Teresa. Ramakrishna’s home remains there, still embodying his spirit and worth a visit by anyone interested in knowing about his life and work.

As a young man, he was largely self-taught, having absorbed knowledge of the ancient tradition of India through reading and hearing the religious stories in the Puranas as well as his association with the holy men, pilgrims and wandering monks who would stop at Kamarpukur on their way to Puri and other holy places. In time he became famous throughout India for his ability to expound and elucidate the most subtle aspects of that profound and vast tradition. It was not uncommon in the years of his maturity for pundits from all over India to come and ‘test’ his knowledge. Invariably, they were astonished by the ease and eloquence with which he addressed their questions. It appeared that his first-hand spiritual experiences were more than adequate when it came to explaining the scriptures of ancient India. In this way he was able to remove all doubt about their meaning and, indeed, his own authority.

By the late nineteenth century India had been governed for almost four hundred years by two of the great world empires— the Mughals and the British. Each had fostered a foreign religion and culture in India which, in time, had been absorbed into Indian civilization. The genius of Ramakrishna was to restore and reaffirm the ancient Hindu culture from its spiritual source.

It would be hard to overestimate the impact that the life, presence and teaching of Sri Ramakrishna had on the formation of the modern India we know today. It was as if the sleeping giant of Indian culture and spirituality—certainly one of the foremost cultures of the ancient world—had been re-awakened and empowered to take its rightful place in modern times. Within a generation of his death, Gandhi’s ‘quit India’ movement was in full bloom. The poetry of Tagore as well as countless manifestations in theatre, music, philosophy and civil discourse were becoming known to the world at large. Over one hundred years ago Swami Vivekananda (the Narendranath of our text) travelled to the West to take part in the first Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago in 1893. He established in America the first Vedanta Centres, which have spread throughout the world, with major centres in Southern California. Even today the influence of India (and ultimately, of Ramakrishna) can be heard in the poetry and music of Allen Ginsburg and the Beatles, to mention only a few artists. It is hard to imagine the emergence of India on the world stage without the spark that was provided by Ramakrishna’s brilliance. Perhaps, some may doubt that India—the most populous democracy of our time, brimming with vitality and creativity—could owe so much to one saintly man, long gone, who lived a life of such utter simplicity. Yet I believe that is exactly the case.

It has been said that when a great man dies, it is as if all of humanity—and the whole world, for that matter—were witnessing a beautiful, timeless sunset. At that moment ‘the great matter of life and death’ is revealed, if not explained and understood. By bearing witness to that event, perhaps we understand a little better our own mortality, its limits and possibilities. The Passion of Ramakrishna is meant to recount in this highly abbreviated work, his suffering, death and transfiguration as they took place during the last few months of his life.

In this work, the words of Ramakrishna are taken up by the Chorus. Sarada Devi was his wife and lifelong companion. M. (his real name was Mahendranath Gupta) was the disciple who kept a close record of his meetings with Ramakrishna, later published as The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. Dr Sarkar [Dr Mahendralal Sarkar] was his attending physician. The two disciples who sing small solo parts are unidentified in the text.