Professor Muhammad Daud was born in Lahore, Pakistan. Rahbar, meaning ‘Guide’, is a pen-name adopted by him. From his great-grandfather to his father, all were teachers of Arabic and Persian literature. Even at the age of 16, he prepared and read a research paper at an All India Oriental Conference in Benaras. He had his education at the Government College in Lahore followed by the Oriental College of the Punjab University. He then went to Cambridge University in England, and in 1953 got his PhD in Oriental studies. His teaching profession took him to many places like the McGill (Canada), Ankara (Turkey), Hartford Seminary Foundation, the University of Wisconsin and the Northwestern University. In Boston University he has been Associate Professor of World Religions in the School of Theology since 1968. His area of interest and research are as varied as religion, aesthetics, folk religion, essential religious phenomena, comparative religions, folk mysticism and Muslim biography. He has some books to his credit.

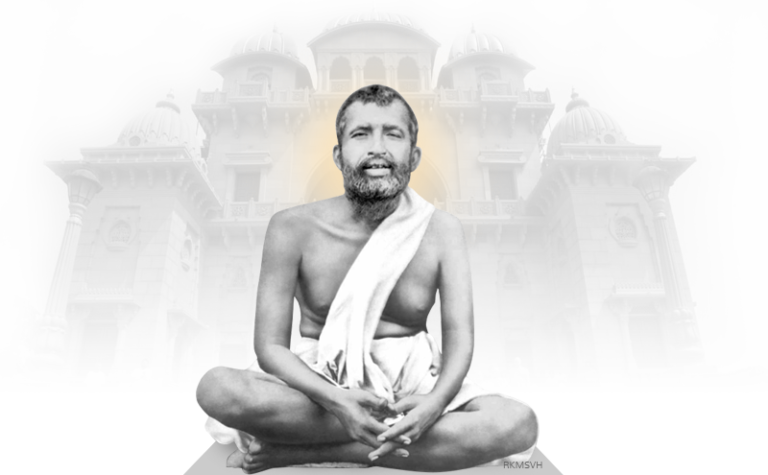

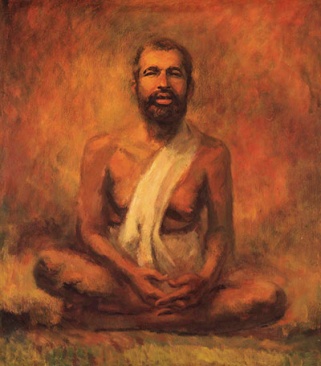

Jesus is remembered as the Son of Man. In the recorded history of religion, Sri Ramakrishna shines as a devotee of the Divine Mother. He should, therefore, be remembered as the Son of Woman.

Four miles north of Calcutta, in the Garden of Temples at Dakshineshwar, he began his devotions to Mother Kali and went into rapture when yet only a child. His life from then on is an open book filled with a moving story of worship and adoration. His revelation of the benign Mother of the Universe is a consummation of the spiritual aspirations of matriarchal India.

Like a magnet, Sri Ramakrishna attracted ardent disciples. More than thirty of them maintained intimate association with him. Hundreds of them derived solace and blessing by beholding him and talking to him.

I have read some delightful portions of the one-thousand-page Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. This marvellous volume has extraordinary revelations. Immediately one recognizes a cherishable friend in Sri Ramakrishna. His open, passionate, and transparent devotion humbles and chastens us. He is no common mortal. He is a man of phenomenal gifts. His presence is a haven. His conversations, recorded abundantly in the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna by his disciple M., are charming, inspiring. Their literary merit is due to the inspired goodness of Sri Ramakrishna. …

We turn now to another genuine quality of Sri Ramakrishna : renunciation. It is perhaps the virtue most vigorously rejected by the politicized civilization of the emerging world. It is condemned by political activists as if it were an adoption of the way of unconcern. The political activists have to go through selfsearching to realize that much of the fever and scramble of politics is a symptom of sick spirit. The implementation of the great movement of democratic thought in the world is not simply a matter of equal opportunity to cultivate ambition. Democratic freedom must learn to respect the freedom to renounce. Perhaps it is true to say that in America today, austere forms of creative renunciation are virtually proclaimed illegal. A mendicant spiritual would be looked upon as a vagrant and a parasite. This is tragic. The excessively politicized intelligentsia in the modern world will hastily detect in Sri Ramakrishna an ‘escapist quietism’. An observation on those lines will be rejected by anyone who reads a substantial part of the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna. In him we find a bustling renunciation full of excitement, but not escapism or quietism. His life is not one of escape for the soul, rather it is a life busy with fortification of the spirit. His ascetic exercises lead to his faith-building charisma. His experiments with psychology of religion are of both spiritual and scientific value for us. He is not running away from responsibilities in the world, he is handling them with eminent creativity. He exercises the privilege of inspired selection of occupation. He investigates the secrets of spirit and soul by turning to experienced men and women. He meditates and is an alert onlooker. He is not bookish but is assiduous in enquiries as a student of folk religion through listening to recital of sacred mythology, direct observation, rigorous introspection, conversation and, most of all, through devotion.

He does all that and does not ask anybody for a salary or a stipend as a reward. Nobody has a reasonable right to object to this arrangement.

Any society that bans renunciation and detachment of this kind is heading for impaired mental health and low level of faith. For it deprives itself of a needed source of holy contagion and vibrations of serenity. Every society needs a mixture of infection of animation and equanimity. Every society needs contagion of selflessness and meditative inspiration. …

The soldierly masculine civilization of the West will have to go through long historical preparation to provide a natural place for the worship of Divine Mother among believers. Nevertheless the assertion of the feminine element has begun. The Western male is not yet effeminate, although perhaps the Western female has become somewhat masculine. …

I pay tribute to Sri Ramakrishna’s device to attain intimacy with Buddhist, Muslim, and Christian life. He demonstrated his own kind of desires and overtures, as against other possible ways of going about the enrichment and broadening of experience. He went about it in a certain mystical way. It is valid, interesting, and meaningful because its motivation was pure. …

There is a great deal of power politics connected with religion. The scientists and secularists have no doubt contributed much to the removal of dishonesty in religious leadership. But now some of the presumption which used to be the trait of some priests is manifest among many secularist men of science. The autonomy of science and intellect has been overdone. The time has arrived when forces of spirit have to be released. Insight and wisdom are lacking in the intellectual world of today. The faces of secularist scientists seldom have a radiance and magnanimity.

Was not the unsophisticated Sri Ramakrishna a gifted scientist in his own right? In his blissful life we find a happy union of religion and science. …